This is part of an ongoing series of printable pamphlets designed to explain how money flows through public research universities in general and the University of Michigan in particular. The pamphlets are intended to clarify arguments and push back against pervasive and seemingly “common sense” narratives about the crisis of public higher education that impede, rather than advance, meaningful political action. We hope tactics and strategies will emerge from these counter-narratives—after all, we can’t fight what we don’t understand. Download the printable version of this pamphlet here and see the Resources page for the entire series.

In November 2013, the University of Michigan launched its new capital campaign, “Victors for Michigan,” which aims to raise $4 billion from private sources primarily to be deposited in the endowment. If successful, it will be the largest in the history of public higher education, topping U-M’s previous campaign which raised $3.2 billion between 2004-2008. On the surface, big donations and a fat endowment seem great. However, the growing importance of the endowment and the university’s dependence on wealthy donors and Wall Street firms are among the factors transforming the contemporary university from a place of learning and knowledge production to something that looks more and more like a corporation—or, in this case, a global hedge fund.

The endowment is a collection of about 7,800 pools of money that are invested around the world.[1] The returns on these investments are then either reinvested or disbursed to different parts of the university, with each individual fund carrying certain restrictions regarding how it can be spent. These restrictions come from the individual donors, who unilaterally dictate that their money be used to fund a particular kind of scientific research, renovate a particular campus building, endow a specific professorship, and so on. A small percentage of the endowment’s returns (4.5%) is applied each year to university operations. Over the past five years, U-M’s $8 billion endowment has contributed an average of less than $300 million a year to operating expenses like professors’ salaries. The administration likes to talk up how 20% of this contribution goes toward financial aid, but $60 million is a drop in the bucket when you consider that tuition adds up to over $1 billion a year (and much of that aid is based on “merit” instead of financial need).

Building and managing this enormous investment portfolio is very expensive. Currently, there are 550 employees who work on what U-M calls “development activities,” including 175 “development officers” who engage directly with potential donors.[2] On top of that, the investment office has 18 employees who are paid a total of $2.7 million annually to oversee the university’s financial assets (in addition to the fees they pay to external fund managers).[3] Yet another expense comes from setting up regional offices around the U.S. and satellite offices in other countries.[4] All of these major expenditures are part of the rapid growth of administration relative to other areas of the university (such as instruction) over the last four decades. Add to that the cost of fancy events, like the “Victors for Michigan” launch party, which cost upwards of $800,000.[5] Donors don’t just hand over their money, so the university has decided it’s willing to spend hundreds of millions of dollars to encourage them to do so.

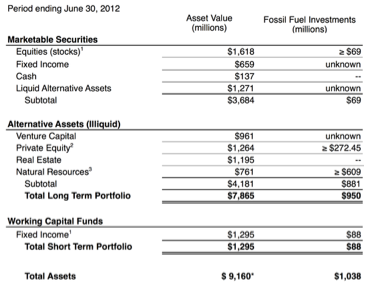

At the University of Michigan, as at other institutions, funds are invested with regard to optimal profitability (even so, the endowment actually lost money in 2001, 2002, 2009, and 2012). As U-M’s chief investment officer recently declared, “We try to be blind to social factors.”[6] This means that the university, and consequently students, are literally profiting off of risky and unethical investments, including the fossil fuel industry, the occupation of Palestine, and real estate speculation around the world.[7] A look at U-M’s “Report of Investments” shows that the university is invested in everything from Mitt Romney’s Bain Capital to the tar sands of Canada (in total, U-M has over $1 billion in fossil fuels).[8] The constant pressure on investment managers to produce adequate returns pushes money into schemes that many members of the university community would actively oppose if they knew. There is no such thing as the Ivory Tower—the university is inseparable from mass layoffs at home and CO2 emissions around the world.

Despite this, the endowment has become a source of pride and sign of stability for institutions like U-M. Much like a corporate CEO announcing quarterly profit margins, the university president now annually releases the latest endowment totals. Today’s university president has turned away from education and increasingly looks like a glorified—and well-remunerated—fundraiser. At the same time, as the university increasingly seeks to attract wealthy alumni and philanthropists it listens to and values their voices and opinions over those of current students and workers. As a result, it not only begins to resemble its corporate sponsors but also feels the need to neutralize disagreement and suppress dissent by those who the donations are supposed to benefit. The endowment makes the university less democratic and less accountable to its community.

The ramifications of this corporate takeover of the university are apparent in the recent “gift” from Charles Munger, the Vice Chairman of the investment firm Berkshire Hathaway. In 2013, Munger pledged $100 million to build a new dormitory for graduate students at U-M. But the building will ultimately cost $185 million, which means the university will have to borrow, and thus pay interest using student tuition on, nearly half the price.[9] Nevertheless Munger, as the donor, got to design the building, which will be organized into 7-person luxury suites that will rent for about $1,000 per person per month, placing them far outside of the reach of grad student instructors living off of their stipends. Unsurprisingly, student responses to the plan have ranged from unenthusiastic to livid. Despite student criticisms, the university has pressed on and the dorm is set to open in 2015.

The administration says the endowment is a key part of the university’s finances. This statement is misleading at best. What’s certainly true is that the administration dedicates more and more of the university’s resources to managing these funds, while at the same time increasingly exposing itself to the fluctuations of the global financial markets. The proof is right in front of our eyes—even as U-M has brought in more and bigger donations, tuition has continued to rise faster than the rate of inflation, pricing out working class and underrepresented minority students. If we are serious about making this university public, the administration’s financial model has to change.

Notes

1. University of Michigan Public Affairs, “University of Michigan Endowment Q&A,” October 2013. ↩

2. Peter Shahin, “Jerry May: Selling Blue for Green,” The Michigan Daily, November 12, 2013. ↩

3. University of Michigan Salary Search, “Department: Chief Investment Officer,” 2013-2014. ↩

4. Sam Gringlas, “Building Networks, Building the University,” The Michigan Daily, March 17, 2013. ↩

5. “Victors for Michigan Campaign Launch Events Cost At Least $750,000,” The Michigan Daily, November 13, 2013. ↩

6. Kellie Woodhouse, “10 Things You Should Know About University of Michigan’s Multibillion Dollar Endowment,” Ann Arbor News, March 26, 2013. ↩

7. Giacomo Bologna, “Group Wants to Rid Endowment of Investments in Fossil Fuels,” The Michigan Daily, March 27, 2013; SAFE, “Support Divestment, Support Human Rights,” The Michigan Daily, March 16, 2014. ↩

8. University of Michigan, “Report of Investments,” June 30, 2012. ↩

9. Student Union of Michigan, “Why We Should Say No to the Munger Dorm,” The Michigan Daily, October 30, 2013. ↩

Download the pamphlet for printing: The Darker Side of University Endowments PDF

Pingback: Thursday Links! | Gerry Canavan

Pingback: Weekend Reading | Backslash Scott Thoughts

Reblogged this on CACHE and commented:

As higher education activists, we all need to sit down and take some time to understand the economic realities of our academic institutions as well as the lenders and guarantors of our debts. We’re ever thankful to the Student Union of Michigan for their work in university economics. And lest we turn away from the fine print of our own university budgets out of the rampant fear of indecipherable joylessness, we should remember what David Foster Wallace says about boredom (and that there’s something superhuman on the other side of it): “The underlying bureaucratic key is the ability to deal with boredom. To function effectively in an environment that precludes everything vital and human. To breathe, so to speak, without air. The key is the ability, whether innate or conditioned, to find the other side of the rote, the picayune, the meaningless, the repetitive, the pointlessly complex. To be, in a word, unborable. It is the key to modern life. If you are immune to boredom, there is literally nothing you cannot accomplish.”

Pingback: Adieu, Mary Sue! A Critical Look at the Coleman Legacy | Student Union of Michigan

Pingback: Civility and Racism at the University of Michigan | Student Union of Michigan